Update from the vernal pool: Wood frogs have hatched!

One of the notable species that rely on our local vernal pools for reproduction is the wood frog (Rana sylvatica), an amazing species whose populations can be found north of the Arctic Circle!

For many, the coming of spring is signaled by the emerging spring ephemerals or the song of the red-winged blackbird. For me, it has always been the spring amphibian migration. As warmer days and nights and heavy rains wake sleeping amphibians, a select group begin to make their way to woodland vernal pools. These temporary pools form in depressions created by the melting snow and spring rains, and are not connected to a permanent water source like a lake or stream. Since vernal pools often dry out by summer, fish cannot live in these habitats, making a safer nursery for amphibians and invertebrates.

One of the notable species that rely on vernal pools for reproduction is the wood frog (Rana sylvatica). The wood frog is an amazing species whose populations can be found north of the Arctic Circle. During the winter, wood frogs will bury themselves under loose leaf litter or find a shallow burrow. Within 5 minutes of freezing, glucose in the wood frog’s liver and leg muscles, as well as urea, are released into the blood and other tissues, essentially acting like antifreeze and preventing cell damage. Like other vernal pool breeders, above-freezing temperatures and rain signal the wood frog to begin migrating, sometimes 400-800m, towards vernal pools. 80-85% of individuals will return to their natal (place of birth) pool. Males enter first, calling for females.

A mature wood frog

The vernal pool chorus has begun.

Males catch hold of females and grasp them with their forelimbs, amplexus. Amplexed pairs will find appropriate substrates to lay eggs. Often groups of up to 100 individual females will lay their eggs communally. This communal egg mass will help retain heat. Females will lay 200-900 eggs each with males fertilizing externally. Once eggs are laid, adults may hang around the vernal pool for a week or so before dispersing. Eggs are at risk from late-spring freezing temperatures, premature drying of the water source, water acidity (pH < 4.2), and predation by leeches, caddisflies, and turtles.

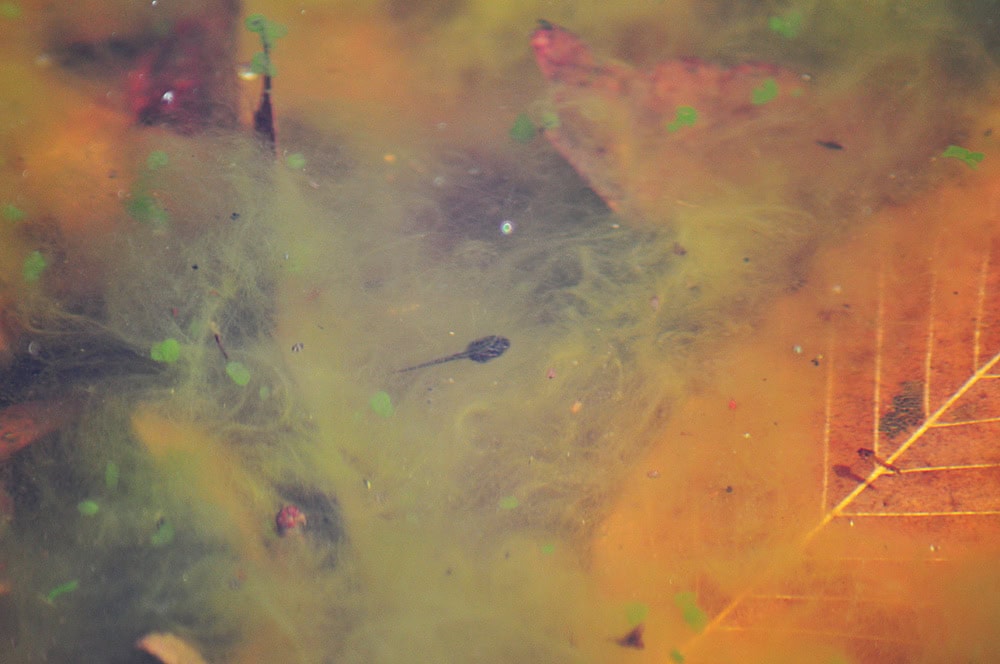

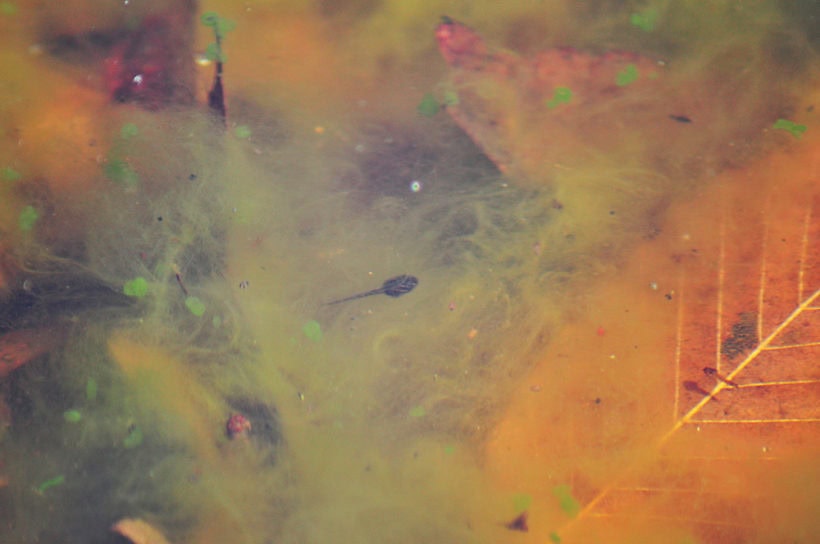

Embryonic development is temperature dependent. Successful hatch-rate is high among frogs, 80-96%. Typically hatching will occur within 3 weeks of eggs being laid. Towards the end of development within the egg, algae will grow on the surface of the egg masses. The larvae (tadpoles) of the wood frog are uniform dark-brown to black, with dark specks and a definite pale lip line. They are small and measure less than 66mm from head to end of tail. Unlike most frog larvae, wood frog tadpoles are omnivorous, feeding on algae, dead plant material, dead or living animals, mole salamander (Ambystoma) eggs, and toad eggs/tadpoles.

Timing of metamorphosis varies with the hydrologic cycle of the vernal pool. The thyroid hormone thryoxin is released into the blood which stimulates metamorphosis. Organs such as gills, tail and fins become redundant and are reabsorbed through cellular death known as apoptosis. 25% of juveniles need to survive to maturity to replace their parents. It takes 2-3 years for a wood frog to reach maturity. Although hatch rate is high among wood frogs, only 2-4% of individuals will reach maturity.

Adults are distinctly marked with a dark mask over their eyes and their body can vary in color from a rusty orange to brownish tan. An adult wood frog can reach a maximum body length of 2in (5.5cm). Wood frogs are terrestrial throughout their entire adult life and can be found both in deciduous and coniferous forests.

As temperatures drop in the fall, wood frogs prepare for hibernation and the cycle begins again.

About the Author

Elissa Schilmeister, Environmental Educator and Volunteer Coordinator

Elissa is a home grown Teatowner, starting as a camper, and going on to be a camp counselor, volunteer, and now staff. Elissa is also a NYS licensed wildlife rehabilitator and EMT.

Leave a Reply