Struggling Through Sap Season

The coming of spring at Teatown is usually heralded by a successful sugaring season. We gave Warren’s Sugar House a thorough scrub down in early February, dutifully set up and sanitized our evaporator pans, and tapped trees before Presidents’ Day. We thrilled to the gentle “tink, tink, tink” of sap falling in our buckets, but a few good days do not a successful sugaring season make.

Why is this tasty tradition getting harder and harder to sustain?

First, let’s unlock the secrets of sap to understand how the lifeblood of trees ends up on our stack of flapjacks. Trees, like all plants, are autotrophs – they produce their own food in the form of glucose or sugar through the miracle of photosynthesis. Using available water in the ecosystem and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, trees (with the help of energy from the sun and chlorophyll) convert these raw materials into glucose and oxygen.

After the growing season in our area, deciduous trees shut down their sugar factories, shed their leaves, and stash the season’s sugar stores in their roots for the winter. As the weather warms, trees take their cue to get the process going for another year of growth.

It is during this emergence from winter dormancy that the syrup producer steps in. Warm sunny days set the sap flowing in a series of fits and starts. Trees send sugars up to the branches to spur leaf development from buds that were set in the late summer, but cold nights cause them to draw the sap back down in the evening, passing the spiles or taps each way.

Sap collectors choose their spile locations carefully, favoring mature Sugar Maples, but being sure not to tap the same exact spot on the trunk for fear of doing lasting damage to the tree. In our area, we tap Sugar Maples, but it is also possible to tap Black and Red Maples as well. All trees (and indeed, all plants!) have sugar in their sap, but the concentration in Sugar Maples is higher than other trees, ranging from 1%—3%.

In a normal year, we collect more than 100 gallons to feed into the evaporator and ultimately produce a few gallons of syrup. It takes anywhere between 40—60 gallons of sap to produce a single gallon of syrup. Over the course of the boiling process, we need to get from sap with a 1% sugar content to syrup with a 67% sugar content, so you can imagine it takes quite a lot of sap to get there!

But this was not a normal year.

The deck was stacked against us in a number of ways: first, a summer drought; second, an unseasonably warm winter; third, almost no snow to speak of; and finally, vital dam repairs on Teatown Lake that required draining the Lake.

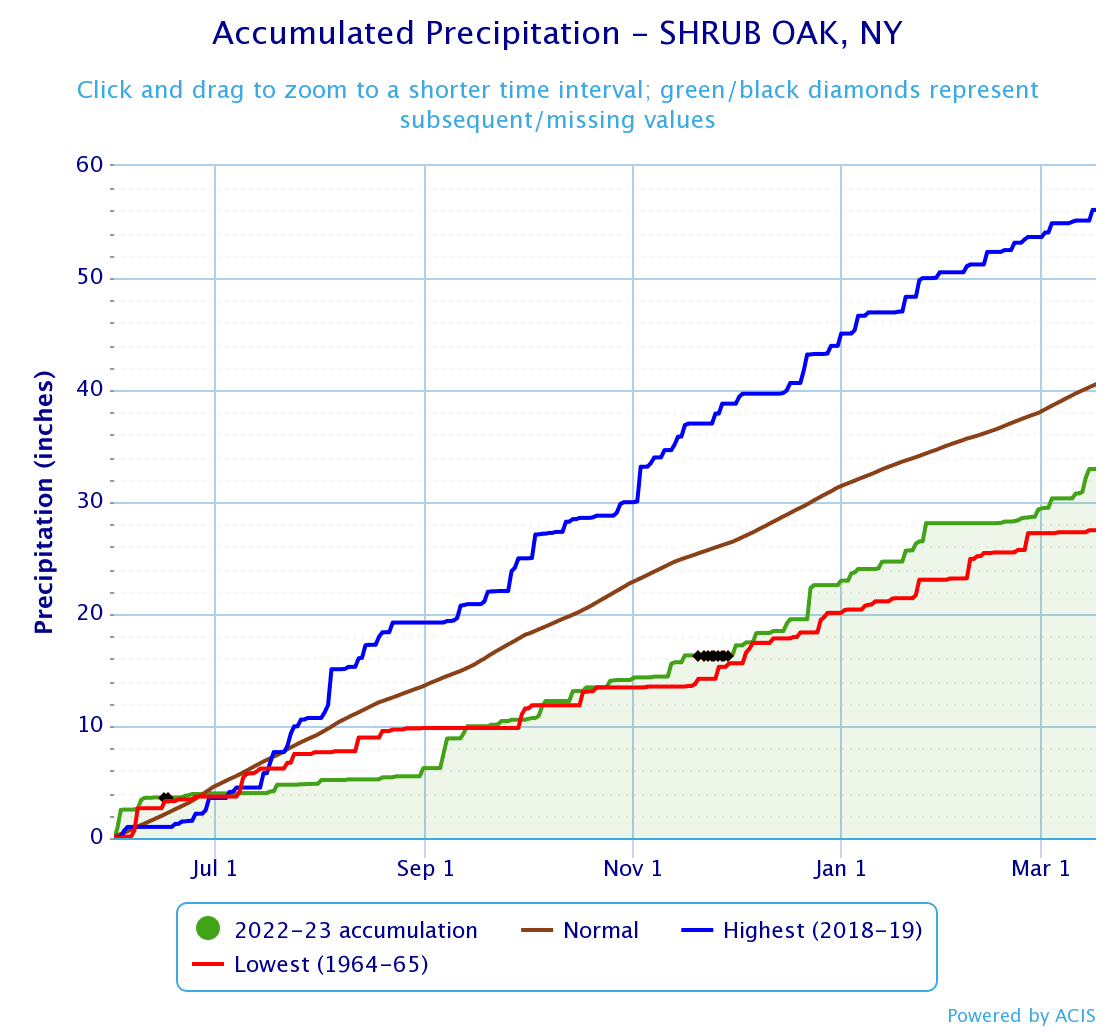

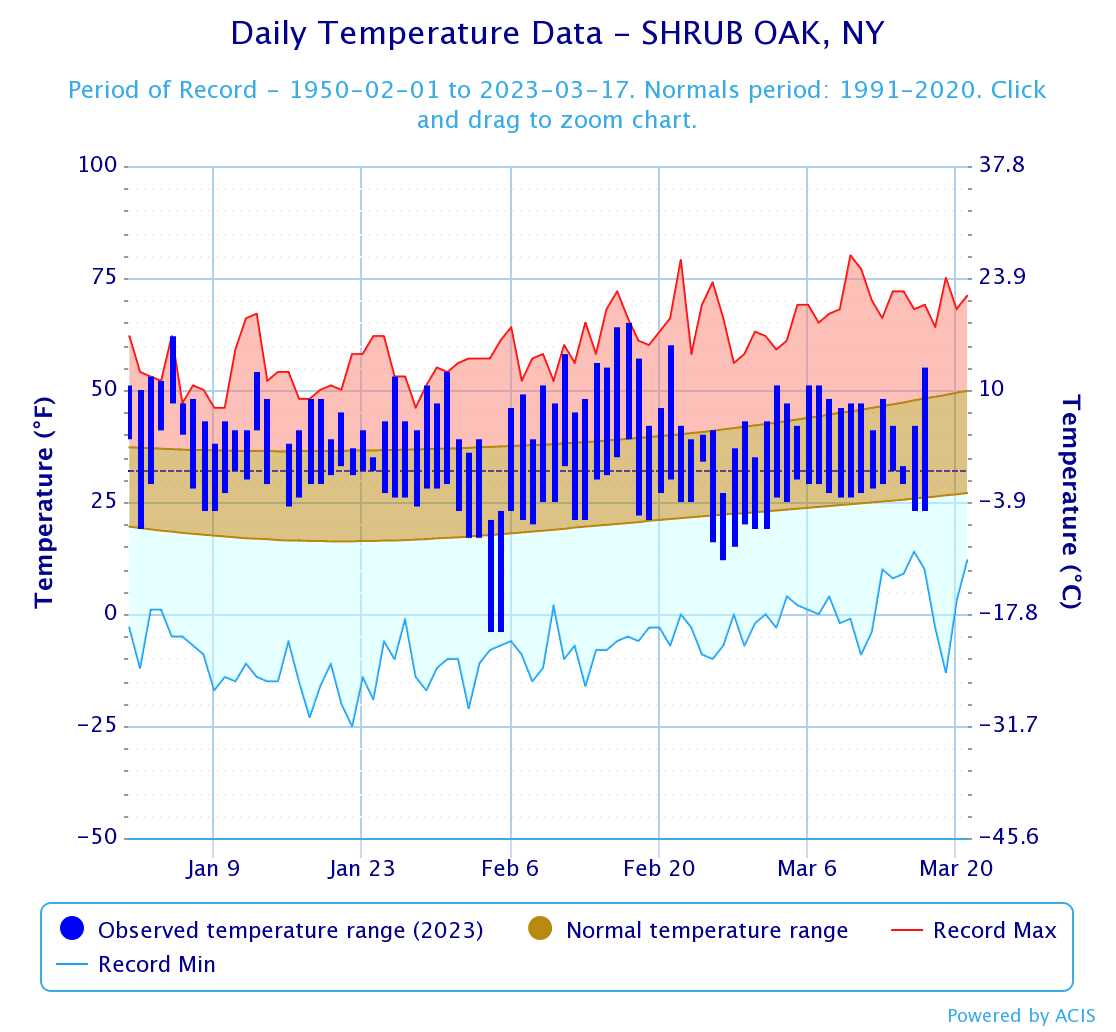

Credit: NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data

On the left, it is clear that we are well below average for precipitation from June until the present. This lack of precipitation paired with the extended period where Teatown Lake was low meant that far less water was available to trees in the ecosystem overall than normal. The right-hand graph shows nearly record-breaking warm winter days with far fewer nights below the freezing mark than is typical. This trend is hardly surprising: “The 10 warmest years in the 143-year record have all occurred since 2010, with the last nine years (2014–2022) ranking as the nine warmest years on record,” according to NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information.

As the climate continues to change, the implications for maple sugaring will be profound. Sugar Maples need cold winters to thrive. As winters in our area warm, we can expect their range to shift northwards. Without major action to address climate change, syrup from southern New York may become a thing of the past.

Be good environmental advocates – push for smart climate legislation so Teatown can preserve the magic of maple syrup production, a tradition with a legacy that stretches back to the Munsee Lenape people who tended these trees for generations.

Leave a Reply