Let’s Talk Turtle!

The Eastern or Woodland Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) is arguably the most identifiable and well-known terrestrial turtle. With contrasting shell colors (often black with striking yellow or orange patterns) these relatively common turtles are found in various habitat types and are easy to see in the wild.

Did you know that Teatown’s Eastern Box Turtles were a part of a turtle tracking study from 2010 to 2013? By marking individuals with transmitters and a unique shell notch code, we were able to re-find these same turtles repeatedly to track their movements.

We learned that turtles that were rehabilitated and relocated to Teatown used habitats just like residents! Relocated turtles did not wander further, and both groups used forests, shrubland, and wetlands similarly. Results of the study were published in 2017.

So, what happened to all those turtles?

Teatown staff have continued to record encounters with individually marked resident box turtles every year since the initial study. Over 14 years, we’ve marked and re-found 71 individuals, which gives us an incredible opportunity to look at box turtle survival. You may think that calculating survival is easy and straightforward, but it isn’t!

Measuring true survival in wild populations is difficult because you would need to observe every single individual every year to know their fate. We know this isn’t reasonable or realistic. Animals can be hard to find! They hide or may wander off-property and back on again. An animal that has “disappeared” from Teatown may have survived but taken up residence somewhere else.

Fortunately, some very smart folks have already solved this problem, recognizing that there are three potential outcomes for any individual after they are initially marked for study. First, they can be found again, and we know they survived (yay!). But, if they aren’t found again, they could have either a) died, or b) survived but been missed by our sampling effort. If we string enough years of data together, we can actually estimate the probability an individual survived even if we didn’t find them.

These estimates are based on the patterns of encounters with other individuals and mathematical modeling. You need a lot of data – dozens of individuals, usually – across several different sampling periods, like years. With enough data you can estimate survival and the probability that you’ll re-find an animal (also known as its recapture probability).

Pretty cool, right? But that’s not even the best part. The most useful thing about these models is that we can then look at survival and recapture probability over time and as a function of some other biological variable that might matter. These could be things like size, age, or sex, which all affect behavior and therefore, survival.

What did Teatown’s data show?

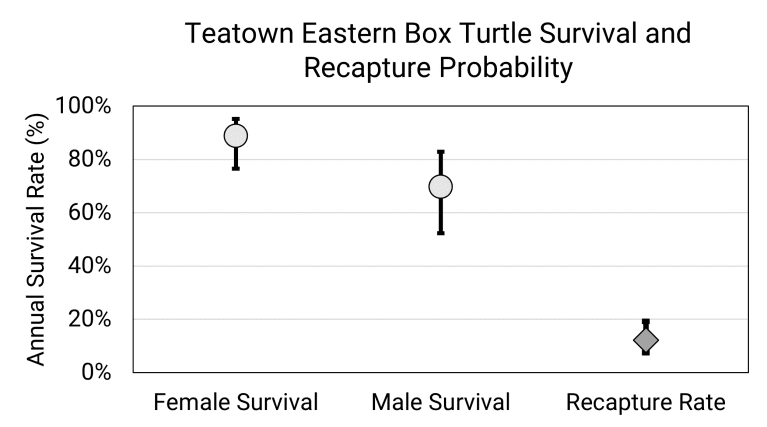

First, survival was vastly different between males and females. Annual survival for female box turtles was very high at 89%. This means that if a female turtle was alive at the beginning of the year, she had an 89% chance of surviving.

You might be worried that 89% sounds too low. It’s important to remember these are estimates for individual turtles, not the entire population, so 89% is very high survival. It’s the equivalent of flipping a weighted coin where 89% of the time you land heads, and 11% you land tails. Each year if you get heads, congratulations! You survived!

This is great news. Females of long-lived, slow-reproducing species like box turtles are very important for persistence of that species locally. Box turtles can live more than 100 years and it can take a decade for a single individual to reach reproductive age. Even then, females lay few eggs and survival of hatchlings is very low. It may take two decades or more for a population to replace the reproductive output of two or three breeding females lost from the population.

For males, their survival was only 69%, or 20% lower than females. Why would males have lower survival than females? Biology, of course! Males tend to be more aggressive toward each other and they wander more in search of mates. Both behaviors are inherently riskier than the homebody style of their female counterparts, reducing survival.

Survival was constant across years for both males and females, indicating no one-off events that would have caused a sudden decrease in survival, like drought, disease, or natural disaster.

What about recapture probability? It was the same for both sexes and only 12%. This means that if the animal was alive at the start of the year there was a 12% chance we encountered it. I told you that some animals were really hard to find!

Figure 1. Teatown Eastern Box Turtle annual survival and recapture probability by sex for mark-recapture data from 2009-2022.

Eastern Box Turtles are NY State-listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), with 21 to 100 occurrences statewide. Their populations are declining regionally due to habitat loss and human-caused mortality, with mower accidents, road collisions, and collection for the pet trade the greatest threats.

Reducing habitat loss and fragmentation by limiting residential and commercial development in areas like Westchester will help preserve available habitat for breeding. Box turtles are homebodies and stay close to their same home range throughout adulthood.

Limiting mowing of fields and shrubby areas to when turtles are hibernating in the winter or early spring will reduce mower mortality. Helping turtles safely cross the road when it’s safe for you to do so will also help reduce road accidents. Turtles should always be moved just off the road in the direction they were already going!

Most importantly, leave wild turtles wild. It is illegal to collect and possess protected plants and animals without a permit — including turtles.

With all of us doing our part to monitor, manage, and protect species like the Eastern Box Turtle we can ensure this species is around for the next generation of people and turtles alike!

Leave a Reply